Disclaimer: This post is not for you if you disagree with the following statement:

Human brain is simply the greatest intellectual quest of all time.

Introduction #

Before setting out on this quest, let’s pause to consider our end goal and direction. How do we understand the brain, and what makes for a good explanation?

The answer that often comes to mind might sound like this:

…so surely the answer to how this thing works is going to have to be at the level of neurons and synapses, right? Neurons and synapses, this thing binds to that thing, changes the shape of a protein, opens the channel, molecules move out — stuff happens. That’s a causal mechanism, right? I can visualize it. We can make an animation and see these almost like physical causality of these bits.

This explanation dives into molecular and cellular mechanisms and provides a perfect causal linkage that’s absolutely scientific and materialistic. And it works. For example, depression involves reduced serotonin at synapses, which led directly to the development of SSRI medications like Prozac, which blocks serotonin pumps to keep more serotonin available. It’s indeed tempting.

But is this the best explanation we can get? Does it have weaknesses? Are there alternatives?

When you start to think about these questions, you’ll soon find yourself in a mire. This explanation misses the big “why”: why are these mechanisms designed this way, and how do they contribute to overall function? From an evolutionary perspective, we as organisms have one sole goal: to survive. Thus we need to understand how the nervous system serves survival advantage.

Second, there are emergent properties. Complex cognitive functions like consciousness and creativity might not be fully explained by just looking at neurons and synapses. Consider the unpredictability of weather as an everyday analogy. We can measure all the individual elements — temperature, pressure, humidity, wind speed, and so on. Each is dictated by physical laws. Yet despite understanding these basic elements, precise long-term prediction remains unachievable. This is not unexpected.

Reductionism has a long history in science — the belief that complex systems can be fully understood by breaking them down into their smallest components. In principle, everything could be explained by physics at the most fundamental level. The success of physics in explaining the physical world with fundamental laws of particles and forces partly encourages a similar approach in neuroscience. But at least for now, there are no fundamental laws of the brain. Maybe we are still waiting for the Newton of neuroscience. Or perhaps the biological brain is simply too complex to be fully understood through reductionism — a harder problem than cosmology. (To the “heretic” who reaches this point: it’s okay to be apostate.)

I hope I have shown you some limitations of classical reductionism. Enter David Marr:

Almost never can a complex system of any kind be understood as a simple extrapolation from the properties of its elementary components. (Marr, 1982)

David argues that to understand a complex system like the brain, one must be prepared to contemplate different kinds of explanations at different levels of description that are linked, at least in principle, into a cohesive whole, even if linking the levels in complete detail is impractical. Understanding a higher level purely through lower-level mechanisms is often impractical, if not impossible. It’s like trying to understand bird flight by studying only feathers. This is why Marr’s approach was revolutionary — it acknowledged the limitations of any single explanation and invited complementary multi-level analysis to understand the system.

The Three Levels #

| Computational theory | Representation and algorithm | Hardware implementation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| David | What is the goal of the computation, why is it appropriate, and what is the logic of the strategy by which it can be carried out? | How can this computation be implemented? In particular, what is the representation for the input and output, and what is the algorithm for the transformation? | How can the representation and algorithm be realized physically? |

| Nancy | What information is extracted and why, what is the input, what is the output and can the output be straightforwardly inferred from the input? Is this inference ill-posed? What extra knwoledge/assumptions can make the problem tractable? What regularities in the world constrain the inference? | How does the system do what it does? i.e. can we write the code to do this? What are the computation representations? How would we find out? | How is the system physically realized in neurons & brains |

The First Level: Computational Theory #

Starting from the top and arguably the most important level is computational theory. As Marr states:

The nature of the computations that underlie perception depends more upon the computational problems that have to be solved than upon the particular hardware in which their solutions are implemented. (Marr, 1982)

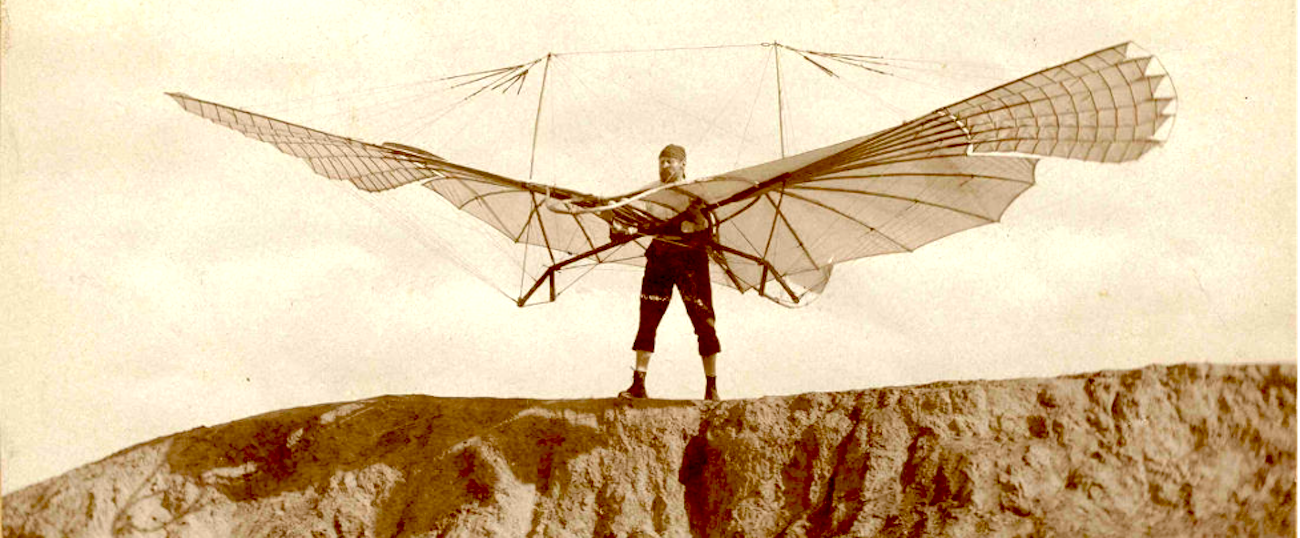

To appreciate the importance of theory, consider the history of flight. Early attempts involved directly mimicking bird wing movements, but they failed. The breakthrough came only after the Wright Brothers systematically studied aerodynamics using wind tunnels and understood the theoretical problem of three-axis control. To understand flight itself, we must understand why feathers and wings have their specific forms rather than just studying their elementary properties.

The power of theory lies in its identification of constraints that must be satisfied and demonstration of how these constraints necessitate certain solutions. In the example of flight, feathers and wings have their current form not by chance or arbitrary design, but because certain properties must exist to achieve lift. Theory also provides implementation-independent principles: aerodynamic principles apply whether the wing is made of feathers or metal, or whether the wing moves horizontally. Satisfying the constraints described by theory is sufficient to generate lift. The world isn’t random beyond comprehension — it has structure, and that structure imposes constraints. Good theories capture fundamental regularities and give us genuine explanatory power.

Now, assuming cognition is ultimately information processing, let’s examine the computational theory such systems must satisfy. Consider a familiar example: the cash register. We need to understand at the computational level what the device does and why it behaves as it does. It’s performing arithmetic, specifically addition. Computational analysis starts with the input to the system and the output from the system. A cash register maps two numbers into single numbers while satisfying:

- Commutativity

$(A+B=B+A)$ - Associativity

$((A+B)+C=A+(B+C))$ - Identity

$(A+0=A)$ - Inverse

$(A+(-A)=0)$

These operations meet constraints we intuitively expect when buying something — for example, the order in which goods are presented to the cashier should not affect the total (commutativity). The constraints capture essential properties of what we want the cash register to do while excluding inappropriate computations. For instance, a cash register shouldn’t perform string concatenation because it’s non-commutative $(A + B = AB != BA = B + A)$.

To summarize, this level asks what problem the system is trying to solve and what constraints it must satisfy. As the saying goes, sometimes you need to step back to see the wood for the trees. As Marr explains:

In the theory of visual processes, the underlying task is to reliably derive properties of the world from images of it; the business of isolating constraints that are both powerful enough to allow a process to be defined and generally true of the world is a central theme of our inquiry. (Marr, 1982)

The Second Level: Representation and Algorithm #

The second level of analysis centers on one important concept: representation.

A famous example illustrating representation is the mutilated-checkerboard problem (Kaplan & Simon, 1990). Consider a checkerboard where two diagonally opposite corner squares have been removed, leaving 62 squares. Now suppose we have 31 dominoes, each able to cover exactly two squares. Can we arrange these dominoes to cover all 62 squares? (Take a moment to ponder this before reading on.)

The answer is no.

To understand why, let’s first consider a simpler “marriage” problem:

A village matchmaker has 32 eligible men and 32 eligible women to pair up for marriages. However, two women leave the village. Can everyone remaining be paired up?

The answer is obviously no — there aren’t enough women to pair with the men. This insight helps us solve the checkerboard puzzle: since each domino must cover one black and one white square (matching), and we have only 30 white squares but 32 black squares, it’s impossible to cover the board completely.

These problems are essentially identical. The key difference? The marriage problem makes the pairing requirement explicit, while the checkerboard’s spatial representation pushes this crucial detail into the background.

As Marr explains:

A representation is a formal system for making explicit certain entities or types of information, together with a specification of how the system does this.

To say that something is a formal scheme means only that it is a set of symbols with rules for putting them together — no more and no less. (Marr, 1982)

The musical score represents a symphony. Arabic numerals (0-9) represent numbers, as do Roman and binary numerals. Each representation captures some aspects of reality through symbols, but not all. Each has its limitations based on how we can manipulate the information. Consider Arabic numerals: they make powers of 10 obvious (10, 100, 1000…) but obscure powers of 2 (2, 4, 8…). They facilitate multiplication, unlike Roman numerals which lack a place value system.

Key points about representation:

- The representation of “reality” is not unique

- Different representation make different information explicit

- The choice of representation can make subsequent operations either easy or hard

After choosing an appropriate representation, we must specify an algorithm for transformation. With addition, we follow rules about adding least significant digits first and “carrying” when the sum exceeds 9. Note that algorithm choice depends mainly on the representation, and multiple algorithms can work with the same representation. Consider determining whether a number is even. Using an array representation $(5 := [1, 1, 1, 1, 1])$, we can implement two different approaches:

# Algorithm 1: Count elements

def is_even_array_1(arr):

return len(arr) % 2 == 0

# Algorithm 2: Pair elements

def is_even_array_2(arr):

while len(arr) > 0:

try:

arr.pop()

arr.pop()

except:

return False

return True

The choice of algorithm depends largely on desired characteristics (like time versus space complexity) and the hardware implementation constraints.

The Third Level: Implementation #

The implementation level received less emphasis from David Marr, likely due to his focus on understanding computational problems. He argued that understanding comes more readily from grasping the nature of the problem than from examining mechanisms. This represents a crucial shift away from the more empirically accessible observations in biological hardware.

However, Marr did note that the same algorithm can be implemented through different technologies. A child and a cash register may use identical algorithms to add numbers, though their physical implementations differ radically. Moreover, certain algorithms naturally suit certain physical structures better than others.

Discussion: The Interplay of Levels #

To recap, Marr’s framework consists of three levels:

- The top level is abstract computational theory, characterized as a mapping from input to output, defined precisely by showing the sufficiency and necessity of constraints

- The middle level involves choosing representations for input and output, plus algorithms for transformation

- At the other extreme lies the physical implementation — how algorithms and representations are realized in hardware

What about the relationship between these levels? As Marr explains:

These three levels are coupled, but only loosely… of course they are logically and causally related. (Marr, 1982)

While complete understanding requires mastery of all three levels, their relative independence means certain phenomena must be explained at specific levels. Consider afterimages (like what you see after staring at a light bulb) — these require explanation primarily at the physical level of vision mechanisms. Being clear about which level suits which subdomain is critical.

For example:

- Neuroanatomy ties principally to the implementation level

- Neurophysiology also relates primarily to implementation, but requires extreme caution when making inferences about representation — we must first understand what information is being represented

Conclusion #

Let me open with a telling anecdote from Gershman (2021):

I once had a conversation with a neuroscientist that went roughly as follows. He told me that we didn’t need psychology to understand the brain; all we had to do was measure what’s going on in the brain, and from those measurements we could derive everything we wanted to know about cognition. I think this point of view is common among neuroscientists, who yearn to free themselves from antiquated notions of mental representations once brain measurement and analysis technology become sufficiently advanced. This, I argue, is a pipe dream born from a naive belief in the innocent eye.

This exchange captures a persistent misconception in neuroscience — that understanding the brain will come solely from observation and measurement. But discovery demands more than looking; it requires thinking. Marr has provided us with a sketch map for approaching the brain from a higher level. While this framework may be incomplete or even flawed in some aspects, it gives us a starting point for organizing our thoughts about this most complex of organs.

Open Questions #

- Can theory lead practice? The success of deep learning seems to challenge Marr’s theory-first approach.

- Does implementation independence hold for intelligence? Would Marr view uploaded minds differently?

- Is the brain really doing information processing? Or are we, like Marr in the age of computers, just seeing the brain through the lens of our era’s dominant technology?

Further Reading #

Main Source #

Marr, David. Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1982.

For a Wider Perspective on Depression #

Sapolsky, Robert. “The Biology and Psychology of Depression.” Stanford University lecture, 2018. https://youtu.be/fzUXcBTQXKM

For Clear Introductions to Marr’s Framework #

Kanwisher, Nancy. “How can we study the human mind and brain: Marr’s levels of analysis.” MIT Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, 2018. https://youtu.be/Di_3pGAveGs

“Marr’s three levels of inquiry.” Course materials, Computational Neuroscience, College of William & Mary. https://apsc450computationalneuroscience.wordpress.com/marrs-three-levels-of-inquiry/

For Understanding Formal Systems #

Hofstadter, Douglas R. “The MU-puzzle.” In Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, 33-66. New York: Basic Books, 1979.

For Critical Perspectives #

Gershman, Samuel J. “Just Looking: The Innocent Eye in Neuroscience.” Neuron 109, no. 14 (2021): 2220-2223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.05.022

Burge, Tyler. “Marr’s Theory of Vision.” In Modularity in Knowledge Representation and Natural-Language Understanding, edited by Jay L. Garfield, 135-153. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987.

Harpaz, Yehouda. “Critique of Vision by Marr.” Human Brain Project, September 26, 1996. https://human-brain.org/vision.html

McClamrock, Ron. “Marr’s Three Levels: A Re-evaluation.” Minds and Machines 1, no. 2 (1991): 185-196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00361036

Acknowledgments #

I am especially grateful to Anmin Yang for many thoughtful and enjoyable conversations. I would also like to thank everyone who read drafts and provided valuable feedback.

Last modified on 2024-11-03